Artist:

John Frederick Peto

(American, 1854 - 1907)

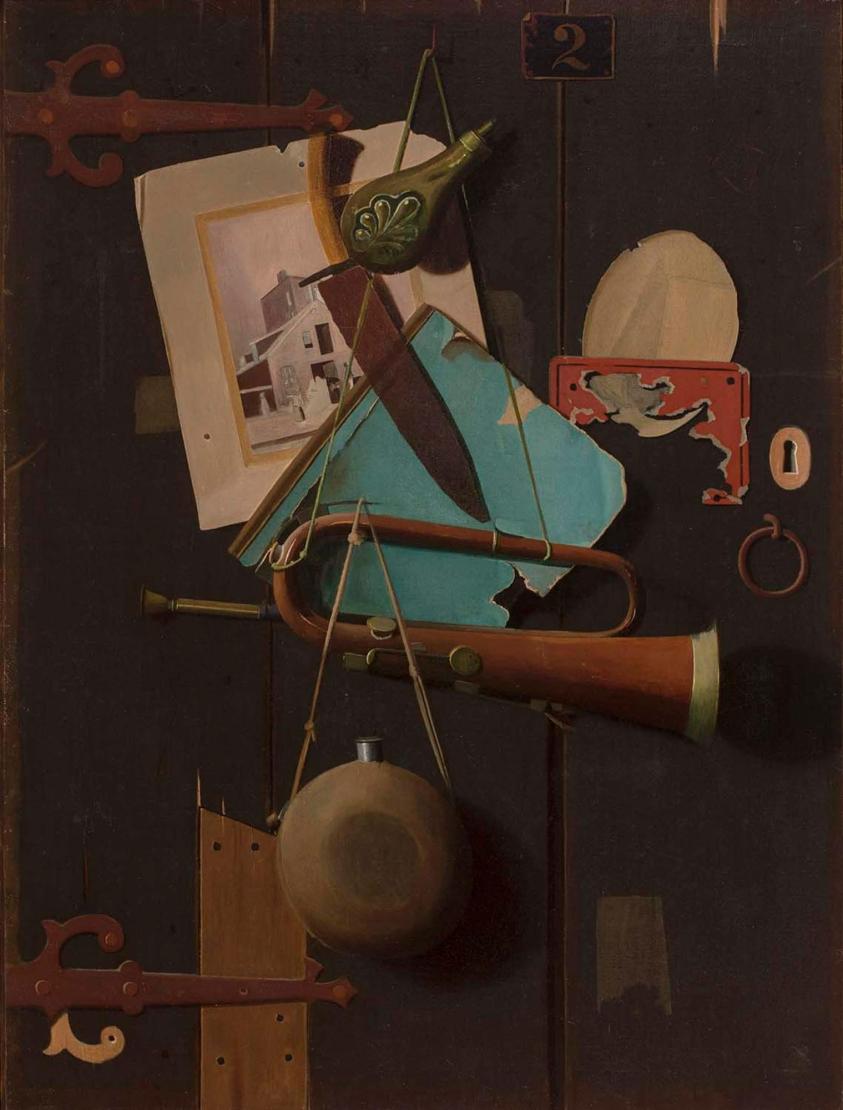

Bowie Knife, Keyed Bugle and Canteen

Medium: Oil on canvas

Date: 1890s

Dimensions:

40 × 30 in. (101.6 × 76.2 cm)

Accession number: 80.3.23

Label Copy:

Philadelphian John F. Peto studied briefly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he met painter William Michael Harnett, whose work is often mistaken for Peto’s own, and vice-versa. Both men favored close-up, informal arrangements of objects symbolizing nineteenth-century masculinity in a trompe l’oeil style that was meant to “fool the eye” into believing the objects were not painted, but real. Peto showed a greater interest in depicting older and more worn objects than Harnett. The torn papers and patched door in this painting show Peto’s interest in infusing his still-life paintings with a sense of the passage of time.

Philadelphian John F. Peto studied briefly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he met painter William Michael Harnett, whose work is often mistaken for Peto’s own, and vice-versa. Both men favored close-up, informal arrangements of objects symbolizing nineteenth-century masculinity in a trompe l’oeil style that was meant to “fool the eye” into believing the objects were not painted, but real. Peto showed a greater interest in depicting older and more worn objects than Harnett. The torn papers and patched door in this painting show Peto’s interest in infusing his still-life paintings with a sense of the passage of time.

Curatorial RemarksThe work of John Frederick Peto is often confused with that of his contemporary and friend, William Michael Harnett. Because Peto's works were often unsigned and undated, many were attributed to Harnett, and sometimes Harnett's better-known signature was forged on them.

Although Peto admired and was influenced by Harnett, the two artists differ stylistically. Both depicted familiar objects in a "trompe l'oeil" technique; however,

Peto's surfaces are often more thickly painted, and his objects are older and more worn than Harnett's. The torn papers and patched door panels in "Bowie Knife, Keyed Bugle, and Canteen" reveal these aspects of his work.

Philadelphian John F. Peto studied briefly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he met painter William Michael Harnett. In 1889, he left Philadelphia for Island Heights, New Jersey, where he lived in a Christian community in which he built a home and studio (now open to the public). He lived there for the rest of his life, often bartering his paintings or selling them to tourists.

The fact that Peto’s works were often unsigned and undated led many of them to be misattributed to Harnett. In fact, there are examples of Harnett’s better-known signature being forged on Peto’s canvases. While both men favored close-up, informal arrangements of objects symbolizing masculinity, their styles were quite different—Peto preferring soft contours, a bright palette, thickly painted surfaces and an overriding concern for light effects, while Harnett favored tighter compositions, crisp brushwork, deeper hues and a more polished surface. The torn papers and patched door in this painting show Peto’s interest in infusing his still-life paintings with the passage of time.

Although Peto admired and was influenced by Harnett, the two artists differ stylistically. Both depicted familiar objects in a "trompe l'oeil" technique; however,

Peto's surfaces are often more thickly painted, and his objects are older and more worn than Harnett's. The torn papers and patched door panels in "Bowie Knife, Keyed Bugle, and Canteen" reveal these aspects of his work.

Philadelphian John F. Peto studied briefly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he met painter William Michael Harnett. In 1889, he left Philadelphia for Island Heights, New Jersey, where he lived in a Christian community in which he built a home and studio (now open to the public). He lived there for the rest of his life, often bartering his paintings or selling them to tourists.

The fact that Peto’s works were often unsigned and undated led many of them to be misattributed to Harnett. In fact, there are examples of Harnett’s better-known signature being forged on Peto’s canvases. While both men favored close-up, informal arrangements of objects symbolizing masculinity, their styles were quite different—Peto preferring soft contours, a bright palette, thickly painted surfaces and an overriding concern for light effects, while Harnett favored tighter compositions, crisp brushwork, deeper hues and a more polished surface. The torn papers and patched door in this painting show Peto’s interest in infusing his still-life paintings with the passage of time.